Chemical reactions happen around us, and in us, everyday. To maintain our body temperature at 98.6 °F (37 °C) when the ambient temperature is cooler, requires heat-generating biochemical reactions that are sensitively regulated. In addition to heat formation, there are four other signs that signal the occurance of a chemical reaction: color change, gas (odor) formation, precipitation of a solid, and light. To help chemists (and chemistry students) manage the vast number of chemical reactions, four categories have been created into which most chemical reactions fall:

- Precipitation

- Acid-Base

- Reduction-Oxidation (RedOx)

- Decomposition

Precipitation reactions occur when the solubility of a product is low and it "falls out of solution" as a precipitate. Observe the precipitation of silver iodide by clicking the Play button in the animation to the left. Since solid reaction products are denser than aqueous solutions, the solid settles to the bottom of the test tube. The saturated solution above the solid is called the supernatant (from Latin - above + swim . . . . float). In the animation, the AgI forms a yellow precipitate while the NaNO3 dissolves in water and does not form a precipitate. Click Play again to repeat the animation.

Is there a way to predict this behavior without "looking up" each products' solubility data?

Yes . . . . the solubility of hundreds of compounds can be predicted with the six solubility rules below.

Start at Rule 1 and proceed until a condition is met for the compound's cation or anion . . . . then,  . . . . a rule with a lower number takes precedence over a rule with a higher number.

. . . . a rule with a lower number takes precedence over a rule with a higher number.

The Solubility Rules

- if the anion is NO3-, HCO3-, C2H3O2-, ClO3- or ClO4-, the compound is Soluble(aq)

- if the cation is an alkali metal cation (Li+, Na+, K+, Rb+, Cs+) or NH4+, the compound is Soluble(aq)

- if the anion is Cl-, Br- or I-, the compound is Soluble(aq) except for AgCl, Hg2Cl2 and PbCl2 .

- if the anion is SO42-, the compound is Soluble(aq) except for SrSO4, BaSO4 and PbSO4 .

- if the cation is Ca2+, Sr2+ or Ba2+, then Ca(OH)2, Sr(OH)2, Ba(OH)2, CaS, SrS, and BaS are Soluble(aq) .

- all remaining salts are Insoluble(s)↓ .

If you know the Soluble(aq) salts and the exceptions for chloride, bromide, iodide and sulfate, you will know the solubility rules because the rest of the salts are Insoluble(s)↓ . Here's another way to view the Solubility Rules ( when a condition is met) . . . .

when a condition is met) . . . .

1. Soluble Anions (X is any cation): XNO3 XHCO3 XC2H3O2 XClO3 XClO4

XCl, XBr, XI except Ag+, Hg22+, Pb2+

XSO4 except Sr2+, Ba2+ and Pb2+

2. Soluble Cations (Y is any anion): LiY NaY KY RbY CsY NH4Y

3. Other Soluble Salts: Ca(OH)2 Sr(OH)2 Ba(OH)2 CaS SrS BaS

Activity: use the solubility rules to predict whether the compounds below are soluble or insoluble. Answer 10 questions correctly to display the Tutorial Complete message.

Activity: predict the products of the following reactions and use the Solubility Rules to assign the state of matter to the reactants and products. After you balance the reaction, click the Show Answer link to check your work.

Barium acetate + Lithium phosphate →

3 Ba(C2H3O2)2 (aq) + 2 Li3PO4 (aq) → Ba3(PO4)2 (s) + 6 LiC2H3O2 (aq)

Solubility Rule # 1 2 6 1

Lead(II) nitrate + Ammonium iodide →

Pb(NO3)2 (aq) + 2 NH4I (aq) → PbI2 (s) + 2 NH4NO3 (aq)

Solubility Rule # 1 2 3 1

Silver nitrate + Potassium chloride →

AgNO3 (aq) + KCl (aq) → AgCl (s) + KNO3 (aq)

Solubility Rule # 1 2 3 1

Strontium acetate + Sodium sulfate →

Sr(C2H3O2)2 (aq) + Na2SO4 (aq) → SrSO4 (s) + 2NaC2H3O2 (aq)

Solubility Rule # 1 2 4 1

Acid-Base Reactions transfer a hydrogen ion, H+, from one reactant (the acid) to another reactant (the base). In Section 2.7 we learned that acids are compounds with an H+ cation. Aqueous solutions of acids are formed when an acid (i.e. HCl) reacts with water to form the hydronium ion (H3O+) . . . .

HCl(g) + H2O(l) → H3O+(aq) + Cl–(aq)

The reaction above is 100% - there are no H–Cl bonds present in the aqueous solution. All of the H's from HCl are bound to water and have formed H3O+. Acids that react 100% with water are called strong acids . . . . the 7 strong acids are HCl, HBr, HI, HNO3, H2SO4, HClO3, and HClO4. Weak acids are acids that are not strong acids . . . HF, HC2H3O2, H3PO4, H2CO3, etc. To reinforce the fact that weak acids only partially react with water, chemists use a double-arrow (⇌) in the equation:

HC2H3O2 (l) + H2O(l) ⇌ H3O+(aq) + C2H3O2–(aq)

This reaction is NOT 100% - there are lots of HC2H3O2 molecules are still present in the aqueous solution. However, some of the H's from HC2H3O2 have combined with water to form H–OH2+.

A base is a compound that produces hydroxide ions (OH–) when it dissolves in water. The strong bases are the hydroxides of the alkali and alkaline earth metals (LiOH, NaOH, KOH, RbOH, CsOH, Ca(OH)2, Sr(OH)2, and Ba(OH)2. These strong bases do not "react" with water, instead, they dissolve in water and . . . . break apart into ions . . . cation(s) and anion(s) 100% . . . .

Ca(OH)2 (s) → Ca2+(aq) + 2 OH–(aq)

Weak bases, however, do react with water to increase the [OH–] in the aqueous solution. Sodium bicarbonate, the weak base in baking soda, reacts with water to produce some hydroxide ions . . . .

NaHCO3 (s) + H2O (l) ⇌ Na+(aq) + OH–(aq) + H2CO3 (aq)

Bases (weak and strong) ❤ acids (weak and strong) . . . . the attraction is 100% (━❤). Acid-base reactions are called neutralization reactions . . . . the products are a salt + water.

HCl(aq) + NaOH(aq) ━❤ NaCl(aq) + HOH(l)

Strong Acid + Strong Base

HCl(aq) + NH3 (aq) ━❤ NH4Cl(aq) + HOH(l)

Strong Acid + Weak Base

2 HF (aq) + Mg(OH)2 (aq) ━❤ MgF2 (aq) + 2 HOH(l)

Weak Acid + Weak Base

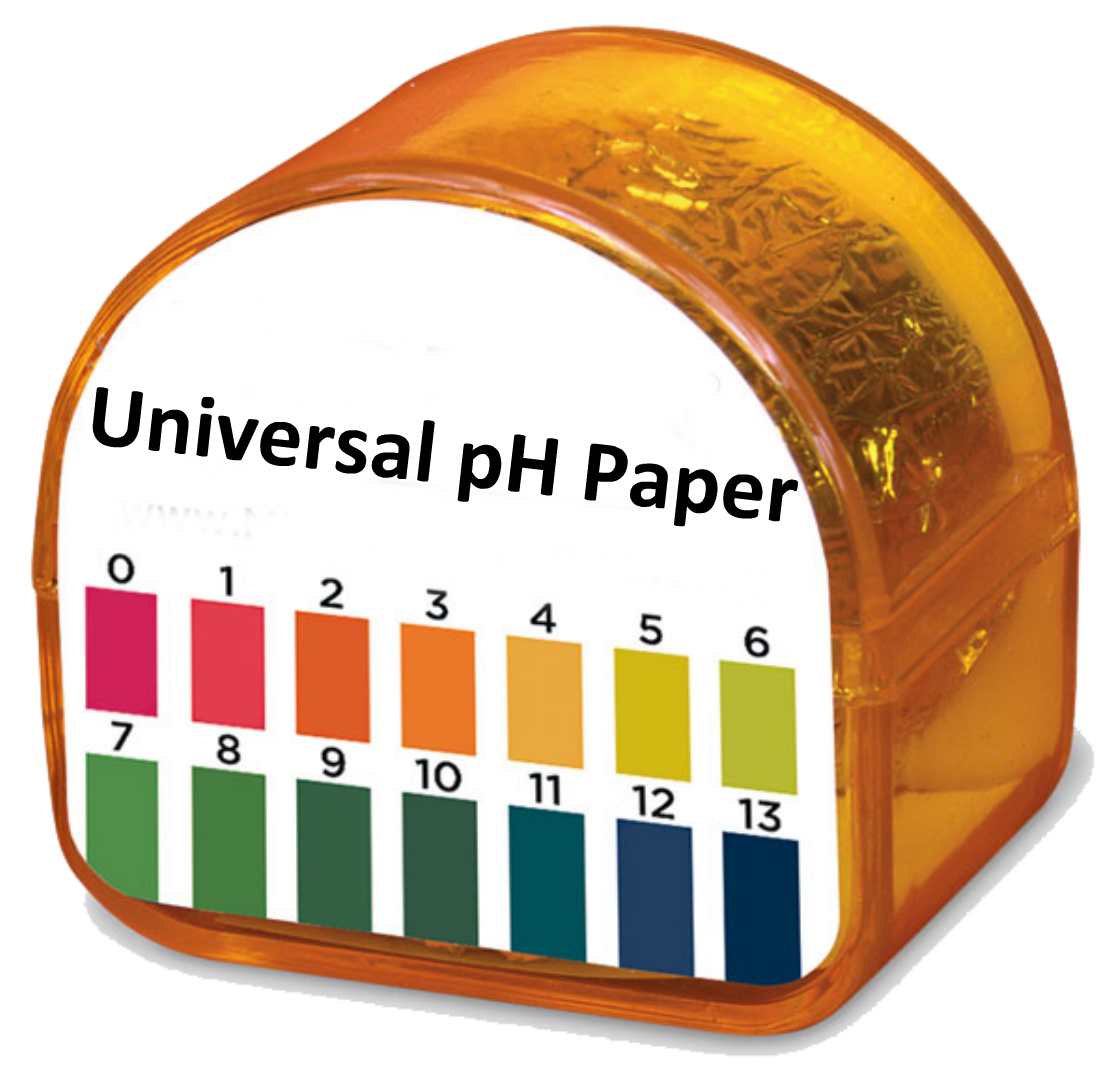

The colors chosen above to represent acids and bases are based on "the Lit mus test". The litmus dye turns red in acid and blue in base. The litmus dye is conveniently available in the form of . . . . strips of paper soaked in litmus and dried.. The litmus test is a quick qualitative measure of acidity - more precise (quantitative) measurements are made with a . The pH of a solution is simply the negative log of the . . . . concentration is expressed as Molarity (moles solute ÷ liter solution). [H+]. The pH of acids is 0 to 7 and the pH of bases is 7 to 14.

The litmus dye is isolated from several species of

- Click/drag the stirring rod on the left to the test tube containing the acid. Dip it into the solution - a drop of liquid clings to the tip of the stirring rod.

- Move the stirring rod / drop to the tip of the flashing white arrow on the left red litmus paper and mouseup.

Was there a color change? Show Answer

- Repeat Step 1. Move the stirring rod / drop to the tip of the flashing white arrow on the left blue litmus paper and mouseup.

Was there a color change? Show Answer

- Repeat the steps above using the stirring rod on the right.

Was there a color change for the red litmus paper?

Show Answer

Was there a color change for the blue litmus paper?

Show Answer

Universal pH paper is "more quantitative" than litmus paper. Universal pH paper has 14 colors and 14 pHs while litmus paper has two colors and the pH is characterized as acidic (0-7) or basic (7-14).

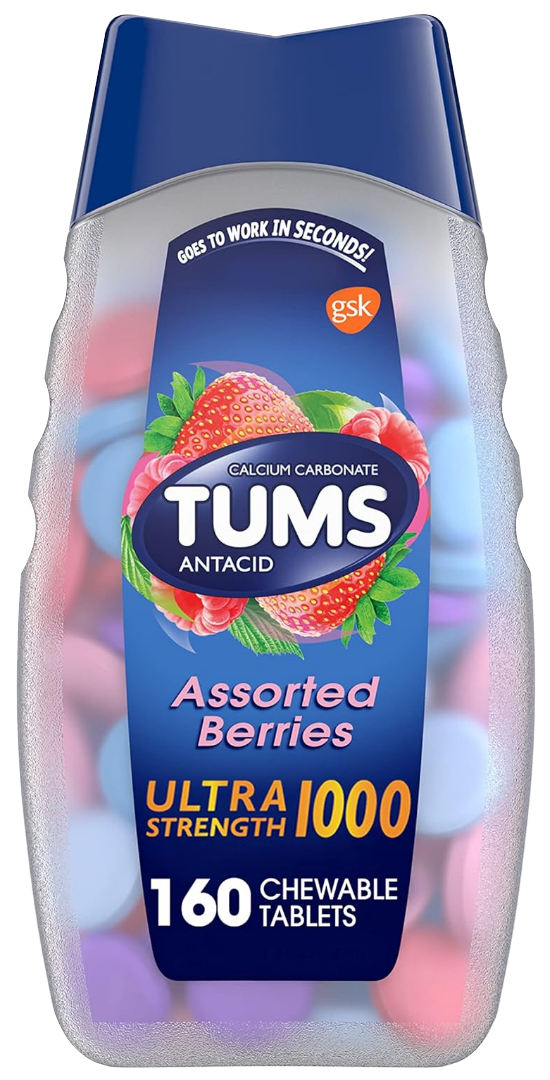

A common acid-base reaction is used by millions of people to combat heartburn. Stomach acid contains approximately 0.03 M H+ ions pH = -log[H+]

pH = - log(0.03)

pH = 1.5 and causes considerable discomfort when it contacts the esophagus. To alleviate this painful situation, we take an antacid (a base) like calcium carbonate the active ingredient in TUMS. Initially the reaction forms carbonic acid, H2CO3, when the H+ and Ca2+ "exchange partners"

CaCO3 (s) + HCl(aq) ━❤ CaCl2 (aq) + H2CO3 (aq)

but H2CO3 is very unstable and decomposes quickly to water and carbon dioxide gas.

CaCO3 (s) + HCl(aq) ━❤ CaCl2 (aq) + H2O(l) + CO2 (g)

Oxidation-reduction reactions - were originally associated with reactions where oxygen, O2, was a reactant. It's not surprising that this reactive gas, comprising 21% of the Earth's atmosphere, plays an essential role in biochemical and environmental processes. When you consume "carbs", you are eating carbohydrates (hydrates of carbon) that have the empirical formula of CH2O. Now, the oxygen that is absorbed through your lungs reacts with these "carbs" and forms CO2 (which you exhale), water and E🗲E R G Y . The reaction below shows the oxidation of glucose (C6H12O6 or 6CH2O) by oxygen.

C6H12O6 (aq) + 6 O2 (aq) → 6 H2O(l) + 6 CO2 (g) + EnergyMolecular Equation(

Oxidation Half-Reaction(+

Reduction Half-Reaction(+

2 Na(s) + Cl2 (g) → 2 NaCl(s)

Na(s) → Na+(s) + e–

Cl2 (g) + 2 e– → 2 Cl–(s)

In the oxidation reaction, electrons are "lost" by the reactant (Na(s)) while the reduction reaction shows electrons "gained" by Cl2 (g). Stated another way, sodium functions as a reducing agent since its electrons "reduce" chlorine. Likewise, chlorine functions as an oxidizing agent by removing electrons from sodium. Half-reactions, like other reactions, are balanced by mass (elements) and charge.

Cl2o(g) + 2 e– → 2 Cl–(s)

(charge = -2) (charge = -2)

There are two mnemonics for remembering oxidation and reduction: Leo says Ger and Oil Rig.

In the reactions above, the two half-reactions were written from the balanced molecular equation . . . . it turns out we can do the reverse ↺ . In fact, seemingly complicated molecular equations are easily balanced from their redox half-reactions. But first, we must be able to determine which element gains electrons and which one loses electrons in the redox reaction. To do this, we must know the "charge" of each reactant element and the "charge" of each product element . . . . only compounds containing elements whose "charge" changes during the reaction are included in the half-reactions. Some "charges" are easily determined - in the example above, both sodium and chlorine are in their elemental (uncharged) state and have a charge of zero. The product of the reaction is NaCl(s) where Na has a +1 charge and Cl has a -1 charge. The initial half-reactions are . . . .

Nao(s) → Na+(s) + 1 e– (oxidation)

Cl2o(g) + 2 e– → 2 Cl–(s) (reduction)

In the oxidation half-reaction, Nao → Na+, a single electron has been lost. In the reduction half-reaction, Cl2o → 2 Cl–, two electrons have been gained – one electron by each Cl atom (in Cl2o). While each half-reaction is currently balanced by atom and charge, it's impossible for the Cl2 (g) in the reduction half-reaction to gain 2 electrons if the reducing agent, Na(s), only loses 1 electron.

Number of electrons lost (oxidation) = Number of electrons gained (reduction)

To account for this inequality, the oxidation half-reaction is multiplied by 2 and added to the reduction half-reaction . . .

2 Nao(s) → 2 Na+(s) + 2 e– (oxidation)

Cl2o(g) + 2 e– → 2 Cl–(s) (reduction)

2 Nao(s) + Cl2o(g) → 2 NaClo(s) (molecular equation)

In the reaction between sodium and chlorine, the charges of the reactant elements (Na and Cl2) and the product ions (Na+ and Cl–) were assigned based on information learned in Section 2.6. However, when the reactant or product consists of two or more elements, each element is assigned an . . . . the hypothetical charge of an atom in a compound if all of its bonds to other atoms are assumed to be 100% ionic..

Consider the reaction where MnO4– is reduced to MnO2, the oxidation numbers of the elements are . . .

Mn+7O-24 (aq)– → Mn+4O-22 (s)

While the oxidation number of O-2 reflects its normal charge in an ionic compound, it is the assignment of +7 and +4 for manganese that needs further explanation . . . . .

Rules For Assigning Oxidation Numbers

- The oxidation number of an atom in its elemental state is zero . . . Li0, Ag0, Ar0, H02, O02, N02, Cl02, F02, I02, Br02, P04, S08

- The oxidation number of a monatomic ion is equal to the ion's charge . . . Cs1+= Cs+1 Mg2+= Mg+2 O2-= O-2

- The oxidation number of a nonmetal . . . .

- Hydrogen:

- +1 when combined with nonmetals . . . H+12O, NH+14, H+1Br

- -1 when combined with metals . . . NaH-1, AlH-13

- Fluorine: -1 always

- Oxygen: -2 except when

- combined with fluorine . . . O+1F-1, O+2F-12

- present in the peroxide ion (O22– ) . . . H+12O-12, Na+12O-12

- Halogens (Cl, Br, I): -1 except when combined with oxygen or another halogen . . . Cl+12O-2

- The oxidation number of a metal . . . .

- The oxidation numbers of Li, K, Na, Rb, Cs and Be, Mg, Ca, Sr, Ba metals are always +1 and +2, respectively.

- The oxidation number of any remaining metal is assigned by creating a simple equation based on one of the following facts:

- the sum of the oxidation numbers in a molecule equals zero . . .

for KMnO4, we can assign K (Rule 4a) and O (Rule 3c) . . . K+1MnO-24

however, the total oxidation number for four oxygens is not -2, it's -8 . . . K+1+1MnO-2-84

now, we can create an equation to solve for the oxidation number of manganese . . . K+1+1Mn+x+xO-2-84 = 0

solving for x gives K+1+1Mn+x+7O-2-84 = 0

the oxidation number of Mn is +7

- the sum of the oxidation numbers in an ion equals the ion's charge . . .

for the dichromate ion, Cr2O72–, we can assign O (Rule 3c) . . . Cr2O-272–

however, the total oxidation number for seven oxygens is not -2, it's -14 . . . Cr2O-2-1472–

now, we can create an equation to solve for the oxidation number of chromium . . . Cr+x+2x2O-2-147 = -2

solving for x gives Cr+62(+6)2O-2-147 = -2

the oxidation number of Cr is +6

Applying these oxidation rules to the previous equation gives +7 and +4 oxidation numbers for manganese.

Mn+7+7O-2-8 = – 14 (aq)– → Mn+4+4O-2-4 = 02 (s)

It is only by assigning oxidation numbers to atoms involved in a redox reaction that we can determine which atoms are changing oxidation states. In this reaction, manganese is being reduced (gaining electrons) . . . . Mn+7 + 3 e– → Mn+4. However, we can't split Mn away from the atoms it is bonded to, so we must write the reduction half-reaction as . . . .

Mn+7O4 (aq)– + 3 e– → Mn+4O2 (s)

While the added electrons balance the oxidation numbers in the oxidation half-reaction above, the atoms are not balanced. The section below will guide you through the process of balancing both charge and atoms in redox reactions.

Balancing Redox Reactions by the Half-Reaction Method

- Write the two redox half-reactions.

- Balance all elements except oxygen and hydrogen.

- Balance the oxygen atoms by adding H2O molecules.

- Balance the hydrogen atoms by adding H+ ions.

- Balance the charge by adding electrons . . . . check that the electrons added equal the oxidation number change that has occurred in the half-reaction.

- If electrons lost ≠ electrons gained, multiply each half-reaction's coefficients by the smallest possible integers so that electrons lost = electrons gained ✓.

- Add the balanced half-reactions together and simplify by removing species that appear on both sides of the equation.

- For reactions occurring in basic media (excess hydroxide ions), carry out these additional steps:

- Add OH– ions to both sides of the equation in numbers equal to the number of H+ ions.

- On the side of the equation containing both H+ and OH– ions, combine these ions to yield water molecules.

- Simplify the equation by removing any redundant water molecules.

- Finally, check to see that both the number of atoms and the total charges are balanced.

Activity: balance the following reactions using the half-reaction method.

Balance the reaction below when the reaction environment is acidic ( ).

NO2 – (aq) + Al(s) → NH3 (aq) + Al(OH)4 – (aq)

After writing each step in the directions above, click the Step button to check your answer.

NO2 – (aq) → NH3 (aq) (reduction)

Al(s) → Al(OH)4 – (aq) (oxidation)

All atoms are balanced except hydrogen and oxygen.

NO2 – (aq) → NH3 (aq) + 2 H2O(l) (reduction)

Al(s) + 4 H2O(l) → Al(OH)4 – (aq) (oxidation)

NO2 – (aq) + 7 H+(aq) → NH3 (aq) + 2 H2O(l) (reduction)

Al(s) + 4 H2O(l) → Al(OH)4 – (aq) + 4 H+(aq) (oxidation)

NO2 – (aq) + 7 H+(aq) + 6 e– → NH3 (aq) + 2 H2O(l) (reduction)

Al(s) + 4 H2O(l) → Al(OH)4 – (aq) + 4 H+(aq) + 3 e– (oxidation)

✓ Check that the electrons added equal the oxidation number change in the half-reaction:

N+3O2 – (aq) + 6 e– → N-3H3 (aq) ✓ N+3 → N-3 is a gain of 6 electrons

Al0(s) → Al+3(OH)4 – (aq) + 3 e– ✓ Al0 → Al+3 is a loss of 3 electrons

Make electrons lost equal electrons gained by multiplying the oxidation half-reaction by 2

NO2 – (aq) + 7 H+(aq) + 6 e– → NH3 (aq) + 2 H2O(l) (reduction)

2 Al(s) + 8 H2O(l) → 2 Al(OH)4 – (aq) + 8 H+(aq) + 6 e– (oxidation)

NO2 – (aq) + 7 H+(aq) + 6 e– + 2 Al(s) + 8 H2O(l)6 H2O(l) → NH3 (aq) + 2 H2O(l) + 2 Al(OH)4 – (aq) + 8 H+(aq)1 H+(aq) + 6 e–

NO2 – (aq) + 2 Al(s) + 6 H2O(l) → NH3 (aq) + 2 Al(OH)4 – (aq) + 1 H+(aq)

Are the atoms balanced?

1 N = 1 N ✓

8 O = 8 O ✓

2 Al = 2 Al ✓

12 H = 12 H ✓

Are the charges balanced?

Reactant charge = -1 . . . . Product charge = -1 ✓

Balance the reaction below when the reaction environment is basic ( ).

Zn2+(aq) + Cr3+(aq) → Zn(s) + Cr2O7 2– (aq)

After writing each step in the directions above, click the Step button to check your answer.

Zn2+(aq) → Zn(s) (reduction)

Cr3+(aq) → Cr2O7 2– (aq) (oxidation)

Zn2+(aq) → Zn(s) (reduction)

2 Cr3+(aq) → Cr2O7 2– (aq) (oxidation)

All atoms are balanced except hydrogen and oxygen.

Zn2+(aq) → Zn(s) (reduction)

2 Cr3+(aq) + 7 H2O(l) → Cr2O7 2– (aq) (oxidation)

Zn2+(aq) → Zn(s) (reduction)

2 Cr3+(aq) + 7 H2O(l) → Cr2O7 2– (aq) + 14 H+(aq) (oxidation)

Zn2+(aq) + 2 e– → Zn(s) (reduction)

2 Cr3+(aq) + 7 H2O(l) → Cr2O7 2– (aq) + 14 H+(aq) + 6 e– (oxidation)

✓ Check that the electrons added equal the oxidation number change in the half-reaction:

Zn+2(aq) + 2 e– → Zn0(s) ✓ Zn+2 → Zn0 is a gain of 2 electrons

2 Cr+3(aq) → Cr+62O7 2– (aq) + 6 e– ✓ 2 Cr+3 → Cr+62O7 2– is a loss of 6 electrons

Make electrons lost equal electrons gained by multiplying the reduction half-reaction by 3

3 Zn2+(aq) + 6 e– → 3 Zn(s) (reduction)

2 Cr3+(aq) + 7 H2O(l) → Cr2O7 2– (aq) + 14 H+(aq) + 6 e– (oxidation)

3 Zn2+(aq) + 6 e– + 2 Cr3+(aq) + 7 H2O(l) → 3 Zn(s) + Cr2O7 2– (aq) + 14 H+(aq) + 6 e–

3 Zn2+(aq) + 2 Cr3+(aq) + 7 H2O(l) → 3 Zn(s) + Cr2O7 2– (aq) + 14 H+(aq)

3 Zn2+(aq) + 2 Cr3+(aq) + 7 H2O(l) + 14 OH-(aq) → 3 Zn(s) + Cr2O7 2– (aq) + 14 H+(aq) + 14 OH-(aq)

3 Zn2+(aq) + 2 Cr3+(aq) + 7 H2O(l) + 14 OH-(aq) → 3 Zn(s) + Cr2O7 2– (aq) + 14 H2O(l)7 H2O(l)

3 Zn2+(aq) + 2 Cr3+(aq) + 14 OH-(aq) → 3 Zn(s) + Cr2O7 2– (aq) + 7 H2O(l)

Are the atoms balanced?

3 Zn = 3 Zn ✓

2 Cr = 2 Cr ✓

14 O = 14 O ✓

14 H = 14 H ✓

Are the charges balanced?

Reactant charge = -2 . . . . Product charge = -2 ✓

Activity: complete the HW 4.2: Balancing Redox Reactions assignment using the half-reaction method.

Decomposition Reactions are reactions where a single reactant breaks apart into two or more products. Previously, we encountered the weak acid, H2CO3, and learned that it readily decomposes to H2O and CO2. A similar decomposition occurs when baker's ammonia (ammonium bicarbonate) is heated.

NH4HCO3 (s) → NH3 (g) + H2O(g) + CO2 (g)

If you have applied hydrogen peroxide to a cut, the cleansing bubbles result from the production of oxygen gas . . . .

2 H2O2 (l) → 2 H2O(l) + O2 (g)